Read: The Missing Millionaire by Katie Daubs 📚A digestable way to learn about early 20th century Toronto rather than turning up any new info on the disappearance of theatre impresario Ambrose Small in 1919. Entertaining enough though. #BookSky

Read: The Missing Millionaire by Katie Daubs 📚A digestable way to learn about early 20th century Toronto rather than turning up any new info on the disappearance of theatre impresario Ambrose Small in 1919. Entertaining enough though. #BookSky

In a closed diner on the main street, an old man with a white beard and a red Christmas hat is sitting at a table doing the accounts. I guess even Father Christmas needs to put aside time for business admin.

Read: The Friends of Meager Fortune by David Adams Richards 📚 Who’d have thought a family saga in in post WW2 New Brunswick logging industry would be this enthralling? The characters are recognisable people, even if the backdrop is unknown. #booksky

Sometimes the music might be great but it’s not helped by the blurb on the website…

EG this from a Bandcamp recommendation: “a tender suite of German trio jazz tinged with Mongolian long song”.

More as I get it.

#MusicSky #wankymusicblurbs

Read: Desert Star (A Renée Ballard and Harry Bosch Novel) by Michael Connelly 📚 Bosch and Ballard content. Solid procedural plus some Ageing Bosch character development. Reliably delivers what you want and then some, and this is why the big name writers get to be the big names. #booksky

Latest edition of the Fuppery Newsletter is live - a twisted, funny retro fictional serial murder mystery told (eventually) in the medium of 1980s village newsletters. open.substack.com/pub/fuppe… #readingcommunity #books #crime

Read: The Widowmaker by Hannah Morrissey 📚Love the seedy, grimey Black Harbor world and this has the usual tapestry of decay, lies and small town secrets. Not quite up there with Hello Transcriber, and there’s gratuitous Oirishness at the end. But better than most. #booksky

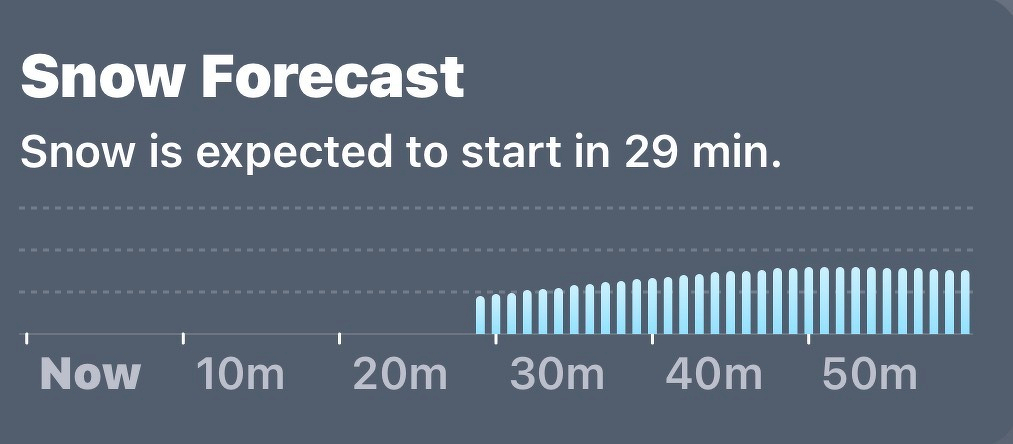

Environment Canada has Very Precise knowledge of snow

Latest in the (fictonal) weird shit my mother wrote about her village - This is prep for the actual serial next week. Kind of tipping the jigsaw pieces out and wondering where they all go) #booksky #writing #iamwriting Greg the geezer

Episode 2 of the Fuppery Newsletter is now live - a twisted, funny retro fictional serial murder mystery told (eventually) in the medium of 1980s village newsletters. Get started while there’s hardly any catching up needed. fupperynewsletter.substack.com/p/fuppery…

I just watched the BBC Celebrity one, and it was laced with celebs getting emotional and saying how cruel and emotional it was (they were paid UKP40k each btw), but you know - it’s just a game. A wildly camp game. With a huge production crew around them. And lest we forget, nobody gets killed. They get given a piece of paper, saying ‘your work here is done’ and they go home to their families. Nobody is being kind, nobody has anything to feel guilty about. These are people who perform on TV for a living performing on TV to be paid. With (mostly) their mates.

And it’s not about the psychology. Anyone with ten minutes attention to the study of human interactions knows we’re terrible at spotting liars. There no interactions we don’t see. Nobody has enough information to make any judgements about anything.

It’s all entirely arbitrary. The hysteria reminds me of the ancient Noel Edmonds ‘game’ show, Deal Or No Deal, with its bullshit about odds. There were no odds. Every single round was a straight 50/50 guess.

I understand that isolating a bunch of people in a house can result in those people getting some kind of group hysteria but let’s not overstate it: the Stanford Prison Experiment was largely fake, let’s remember. But FFS, this was a silly, camp game show. Calling it cruel, stewing in manufactured ‘guilt’, or pretending it offers some kind of psychological insight is just TV’s usual self aggrandisement.

Read: Putin’s People by Catherine Belton 📚TLDR: Putin helped the KGB steal all Russia’s money, oligarchs stole it from the KGB and set up Putin as leader, Putin stole the money from the oligarchs. Putin wins. Authoritative, heavily researched and so so so so detailed. #booksky #bookstodon

Read: You Killed Me First by John Marrs 📚More gloriously fucked up suburban homicide from John Marrs. At one point I feared it might veer into supernatural tropes, but thankfully it was just psychosis. #booksky #bookstodon

A squid-fishing ship goes silent in the Pacific & gangster’s fixer Liu discovers the problem’s worse, and weirder, than he could possibly imagine - but will he escape to tell the tale? My first short story to hit the streets: www.freedomfiction.com/2025/11/s…

Latest in the (fictonal) weird shit my mother wrote about her village - This is prep for the actual serial next week. Kind of tipping the jigsaw pieces out and wondering where they all go) #writing #iamwriting fupperynewsletter.substack.com/p/fuppery…

Latest in the (fictonal) weird shit my mother wrote about her village - This is prep for the actual serial next week. Kind of tipping the jigsaw pieces out and wondering where they all go) #booksky #writing #iamwriting fupperynewsletter.substack.com/p/dossier…

Latest in the (fictonal) weird shit my mother wrote about her village - This is prep for the actual serial next week. Kind of tipping the jigsaw pieces out and wondering where they all go) #booksky #writing #iamwriting fupperynewsletter.substack.com/p/dossier…

Someone on here just told me to ‘let that sink in’.

I went to the front door but there was nothing waiting there. No toilet, no bath and definitely no sink. If you see a poor homeless sink, shivering in the October chill, please let me know.

Latest in the (fictonal) weird shit my mother wrote about her village - This is prep for the actual serial next week. Kind of tipping the jigsaw pieces out and wondering where they all go) #booksky #writing #iamwriting open.substack.com/pub/fuppe…

Read: The Helsinki Affair by Anna Pitoniak 📚Modern day CIA spy-daughter investigates what her CIA spy-father got up to in the cold war. Top flight blend of character, suspense and world. Audiobook marred by a narrator with only a passing acquaintance with many common English words. #bookstodon

Next fragment from the the Fuppery Newsletter is up and going.

It begins. The first instalment of my twisted, funny retro serial murder mystery told in the medium of 1980s village newsletters has just gone up on substack. Getcherluvverly serialised fiction here: The Fuppery Newsletter

Woohoo. Another short story accepted today. I say short. 9000 words…. More as we get it.

#amwriting #HorrorSky #WriterSky

Good audiobook, terrible reader. So far she’s mispronounced antipodean, MI6 (as M16, twice), frequent, Grosvenor and idyll. Does nobody check this stuff? #bookstodon #booksky